Systems thinking for product manager's

📣. Definitions 🔆 What is systems thinking 💡 Systems thinking mindset 🧠 Fundamental concepts of systems thinking ❤️🔥 35% off on PM's Guide

Systems thinking

A new way to view and mentally frame what we see in the world; a worldview and way of thinking whereby we see the entity or unit first as a whole, with its fit and relationship to its environment as primary concerns

Content

Definations

What is systems thinking

Systems thinking mindset

6 Fundamental concepts of systems thinking

Definitions :

- System

A set of components that work together for the overall objective of the whole

- Systems thinking

A new way to view and mentally frame what we see in the world; a worldview and way of thinking whereby we see the entity or unit first as a whole, with its fit and relationship to its environment as primary concerns

Geoffrey Vickers, in 1970, explained the theory more in layman’s terms:

The words general systems theory imply that some things can usefully be said about systems in general, despite the immense diversity of their specific forms. One of these things should be a scheme of classification. Every science begins by classifying its subject matter, if only descriptively, and learns a lot about it in the process . . Systems especially need this attention, because an adequate classification cuts across familiar boundaries and at the same time draws valid and important distinctions which have previously been sensed but not defined. In short, the task of General Systems Theory is to find the most general conceptual framework in which a scientific theory or a technological problem can be placed without losing the essential features of the theory or the problem.

What is a Systems Thinking?

Systems thinking is a vantage point from which you see a whole, a web of relationships, rather than focusing only on the detail of any particular piece. Events are seen in the larger context of a pattern that is unfolding over time.

‐ isee systems, inc.

Systems thinking is a perspective of seeing and understanding systems as wholes rather than as collections of parts. A whole is a web of interconnections that creates emerging patterns.

– Peter Seng

Systems Thinking helps us to move the focus away from events and patterns of behavior (which are symptoms of problems) and toward systemic structure and the underlying mental models

Systems Thinking helps us to find the most important places for intervention to change the long‐term behaviour of a system.

Approach is to

Identify a system - After all, not all things are systems. Some systems are simple and predictable, while others are complex and dynamic. Most human social systems are the latter.

Explain the behavior or properties of the whole system - This focus on the whole is the process of synthesis. Analysis looks into things while synthesis looks out of things.

Explain the behavior or properties of the question to be explained in terms of the role(s) or function(s) of the whole.

Discovering the systems thinking mindset

To begin with, we must understand that any mindset consists of mental models, or concepts, that influence our interpretation of situations and predispose us to certain responses. These models, which are replete with beliefs and assumptions, thus strongly determine the way we understand the world and act in it. The irony is, sections, that we seldom pay attention to them. Even when something in our experience calls them into question— an “unsolvable” problem, perhaps, or an “unmanagable” interpersonal conflict—we miss the call. Those problems and conflicts, patched up for the time being, never really get resolved, and we wonder why success eludes us. Often, not until a crisis hits, driving us deep into ourselves, do we realize we’ve been acting on unfounded beliefs or outmoded assumptions, and finally shift our mindset. But we don’t always catch the obvious lesson: that we need to put ourselves in touch with our mental models, hold them up to the light and look for biases and unsupported “facts,” those things which cause us to misunderstand the world; in short, that we must take an active role in shaping our mindsets, opting for mental models which better “capture” the world we need to understand. It is at this point where the systems thinking mindset comes in.

Mindset and Worldview The beauty of this mindset is that its mental models are based on natural laws, principles of interrelationship, and interdependence found in all living systems. They give us a new view of ourselves and our many systems, from the tiniest cell to the entire earth; and as our organizations are included in that great range, they help us define organizational problems as systems problems, so we can respond in more productive ways. The systems thinking mindset is a new orientation to life. In many ways it also operates as a worldview—an overall perspective on, and understanding of, the world. To develop this mindset, we must first look to three fundamental principles of living systems: that of openness, interrelationship, and interdependence.

6 Fundamental concepts:

Interconnectedness

Synthesis

Emergence

Feedback Loops

Causality

Systems Mapping

1. Interconnectedness

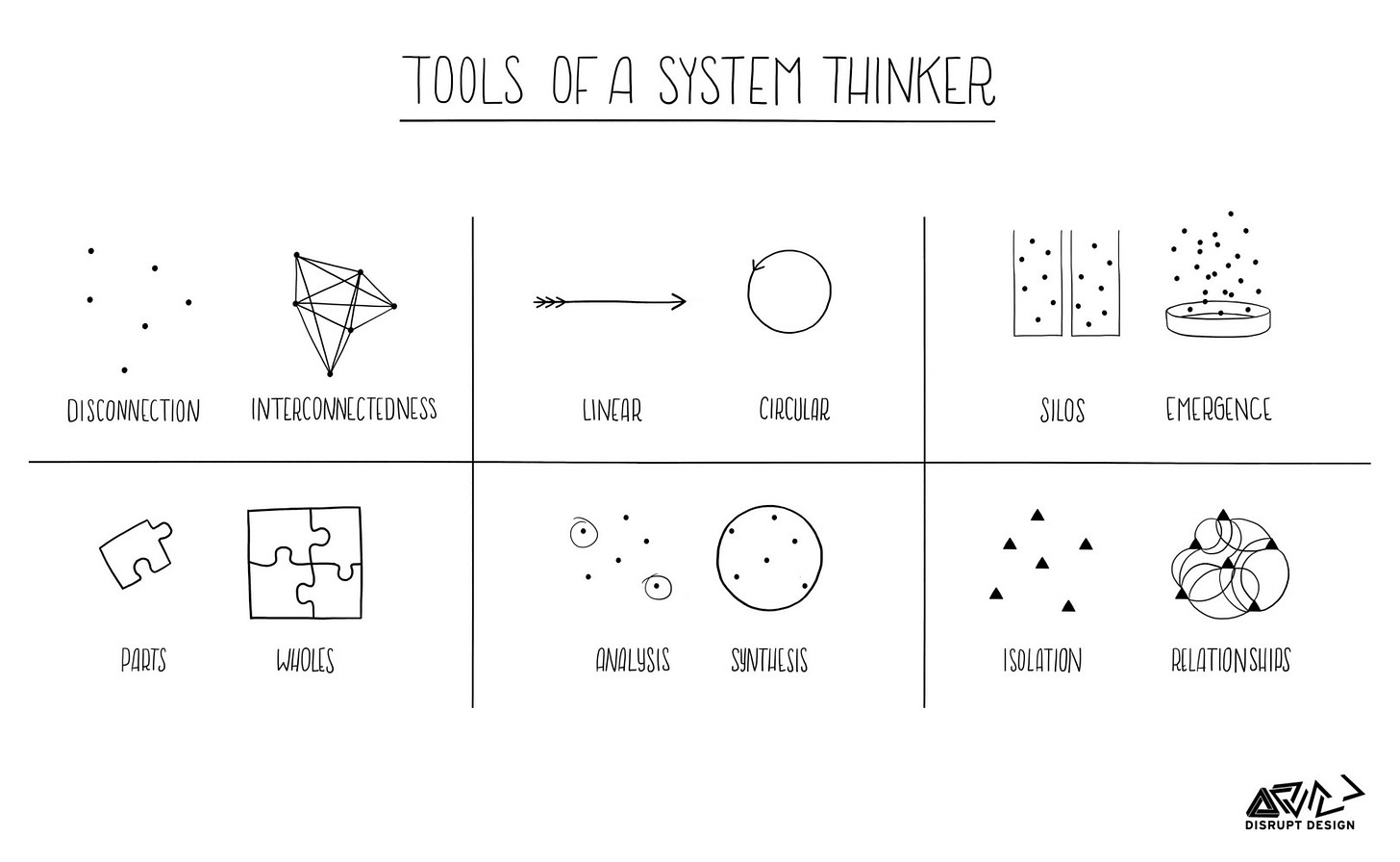

Systems thinking requires a shift in mindset, away from linear to circular. The fundamental principle of this shift is that everything is interconnected. We talk about interconnectedness not in a spiritual way, but in a biological sciences way.

Essentially, everything is reliant upon something else for survival. Humans need food, air, and water to sustain our bodies, and trees need carbon dioxide and sunlight to thrive. Everything needs something else, often a complex array of other things, to survive.

Inanimate objects are also reliant on other things: a chair needs a tree to grow to provide its wood, and a cell phone needs electricity distribution to power it. So, when we say ‘everything is interconnected’ from a systems thinking perspective, we are defining a fundamental principle of life. From this, we can shift the way we see the world, from a linear, structured “mechanical worldview’ to a dynamic, chaotic, interconnected array of relationships and feedback loops.

A systems thinker uses this mindset to untangle and work within the complexity of life on Earth.

2. Synthesis

In general, synthesis refers to the combining of two or more things to create something new. When it comes to systems thinking, the goal is synthesis, as opposed to analysis, which is the dissection of complexity into manageable components. Analysis fits into the mechanical and reductionist worldview, where the world is broken down into parts.

But all systems are dynamic and often complex; thus, we need a more holistic approach to understanding phenomena. Synthesis is about understanding the whole and the parts at the same time, along with the relationships and the connections that make up the dynamics of the whole.

Essentially, synthesis is the ability to see interconnectedness.

3. Emergence

From a systems perspective, we know that larger things emerge from smaller parts: emergence is the natural outcome of things coming together. In the most abstract sense, emergence describes the universal concept of how life emerges from individual biological elements in diverse and unique ways.

Emergence is the outcome of the synergies of the parts; it is about non-linearity and self-organization and we often use the term ‘emergence’ to describe the outcome of things interacting together.

A simple example of emergence is a snowflake. It forms out of environmental factors and biological elements. When the temperature is right, freezing water particles form in beautiful fractal patterns around a single molecule of matter, such as a speck of pollution, a spore, or even dead skin cells.

Conceptually, people often find emergence a bit tricky to get their head around, but when you get it, your brain starts to form emergent outcomes from the disparate and often odd things you encounter in the world.

There is nothing in a caterpillar that tells you it will be a butterfly — R. Buckminster Fuller

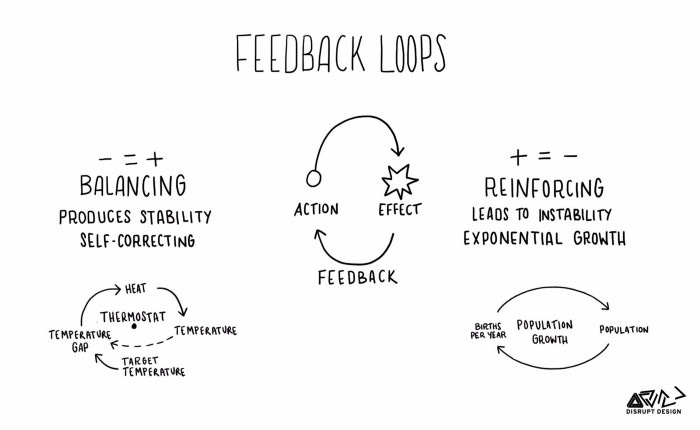

4. Feedback Loops

Since everything is interconnected, there are constant feedback loops and flows between elements of a system. We can observe, understand, and intervene in feedback loops once we understand their type and dynamics.

The two main types of feedback loops are reinforcing and balancing. What can be confusing is a reinforcing feedback loop is not usually a good thing. This happens when elements in a system reinforce more of the same, such as population growth or algae growing exponentially in a pond. In reinforcing loops, an abundance of one element can continually refine itself, which often leads to it taking over.

A balancing feedback loop, however, is where elements within the system balance things out. Nature basically got this down to a tee with the predator/prey situation — but if you take out too much of one animal from an ecosystem, the next thing you know, you have a population explosion of another, which is the other type of feedback — reinforcing.

5. Causality

Understanding feedback loops is about gaining perspective of causality: how one thing results in another thing in a dynamic and constantly evolving system (all systems are dynamic and constantly changing in some way; that is the essence of life).

Cause and effect are pretty common concepts in many professions and life in general — parents try to teach this type of critical life lesson to their young ones, and I’m sure you can remember a recent time you were at the mercy of an impact from an unintentional action.

Causality as a concept in systems thinking is really about being able to decipher the way things influence each other in a system. Understanding causality leads to a deeper perspective on agency, feedback loops, connections and relationships, which are all fundamental parts of systems mapping.

6. Systems Mapping

Systems mapping is one of the key tools of the systems thinker. There are many ways to map, from analog cluster mapping to complex digital feedback analysis. However, the fundamental principles and practices of systems mapping are universal. Identify and map the elements of ‘things’ within a system to understand how they interconnect, relate and act in a complex system, and from here, unique insights and discoveries can be used to develop interventions, shifts, or policy decisions that will dramatically change the system in the most effective way.