Product Logic Model :

Product Goals: Output, Outcome, Impact

Imagine that you work for a charitable organization and you’ve been asked to build a well in a small village that lacks modern plumbing. You’ve been given funding by a foundation that wants to increase the standard of living in this village. They have observed that villagers spend a large amount of time every day walking to the river to carry water. The foundation believes that if the villagers had a well in the center of the village, they wouldn’t have to carry water such long distances anymore, and they could use their time for other activities—ones that would allow them to improve their standard of living.

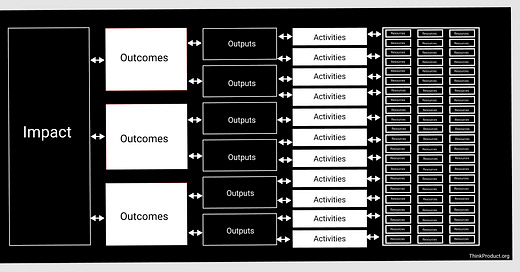

In the social impact sector it’s common to use a model called the Program Logic Model to plan work like this and evaluate the results. In the diagram below you can see the building blocks of that model:

Impact <> Outcomes <> Outputs <> Activites <> Resources

For our well project, the model might be something like this: we plan our resources (the people, materials, money, and other things we need), we undertake a set of activities (traveling to the village, acquiring and transporting our materials, building a well). If all of this goes according to plan, we create the output—the well. If the well works as planned, we achieve our outcome—people in the village spend less time carrying water. That in turn, becomes an important contributor to the impact we seek: a higher standard of living in the village.

Notice that the outcome—people spend less time carrying water—is a change in behavior that creates positive results.

Why do we need all these levels in our model? Although our ultimate target is to improve the standard of living in the village, that target is actually a result of many factors. To see if our work is actually making a difference, we need checkpoints that are smaller, measurable, and more closely connected to the work that we’re doing. That’s where outcomes are important. By setting our outcome as “villagers spend less time carrying water” we have an easier time assessing the quality of our work.

Outcomes

When you’re creating hypotheses to test, you want to try to be very specific regarding the outcomes you are trying to achieve. Lean Product teams focus less on output (the documents,even the products and features that we create) and more on the outcomes that these outputs create: can we make it easier for people to log into our site? Can we encourage more people to sign up? Can we encourage greater collaboration among system users?

Together with your team, look at the problem you are trying to solve. You probably have a few high-level outcomes you are hoping to achieve (e.g., increasing signups, increasing usage, etc.). Consider how you can break down these high-level outcomes into smaller parts. What behaviors will predict greater usage: more visitors to the site? Greater click-through on email marketing? Increasing number of items in the shopping cart? Some- times it’s helpful to run a team brainstorm to create a list of individual outcomes that, taken together, you believe will predict the larger outcome you seek.

Progress = outcomes, not output

What is it? Features and services are outputs. The business goals they are meant to achieve are outcomes. Lean Product Management measures progress in terms of explicitly defined business outcomes.

Why do it? When we attempt to predict which features will achieve spe- cific outcomes, we are mostly engaging in speculation. Although it’s easier to manage toward the launch of specific feature sets, we don’t know in any meaningful way whether a feature is effective until it’s in the market. By managing to outcomes (and the progress made toward them), we gain insight into the efficacy of the features we are building. If a feature is not performing well, we can make an objective decision as to whether it should be kept, changed, or replaced.

How does it work, really ?

outcome-focused work: the hypothesis statement. The hypothesis statement is the starting point for a project. It states a clear vision for the work and shifts the conversation between team members and their managers from outputs (e.g., “we will create a single sign-on feature”) to outcomes (e.g., “we want to increase the number of new sign-ups to our service”).

The hypothesis statement is a way of expressing assumptions in testable form. It is composed of the following elements:

Assumptions

A high-level declaration of what we believe to be true.

Hypotheses

More granular descriptions of our assumptions that target specific areas of our product or workflow for experimentation.

Outcomes

The signal we seek from the market to help us validate or invalidate our hypotheses. These are often quantitative but can also be qualitative.

Personas

Models of the people for whom we believe we are solving a problem.

Features

The product changes or improvements we believe will drive the outcomes we seek.