5 C’s of Product Pricing

Pricing is all about customer value - Warren Buffett

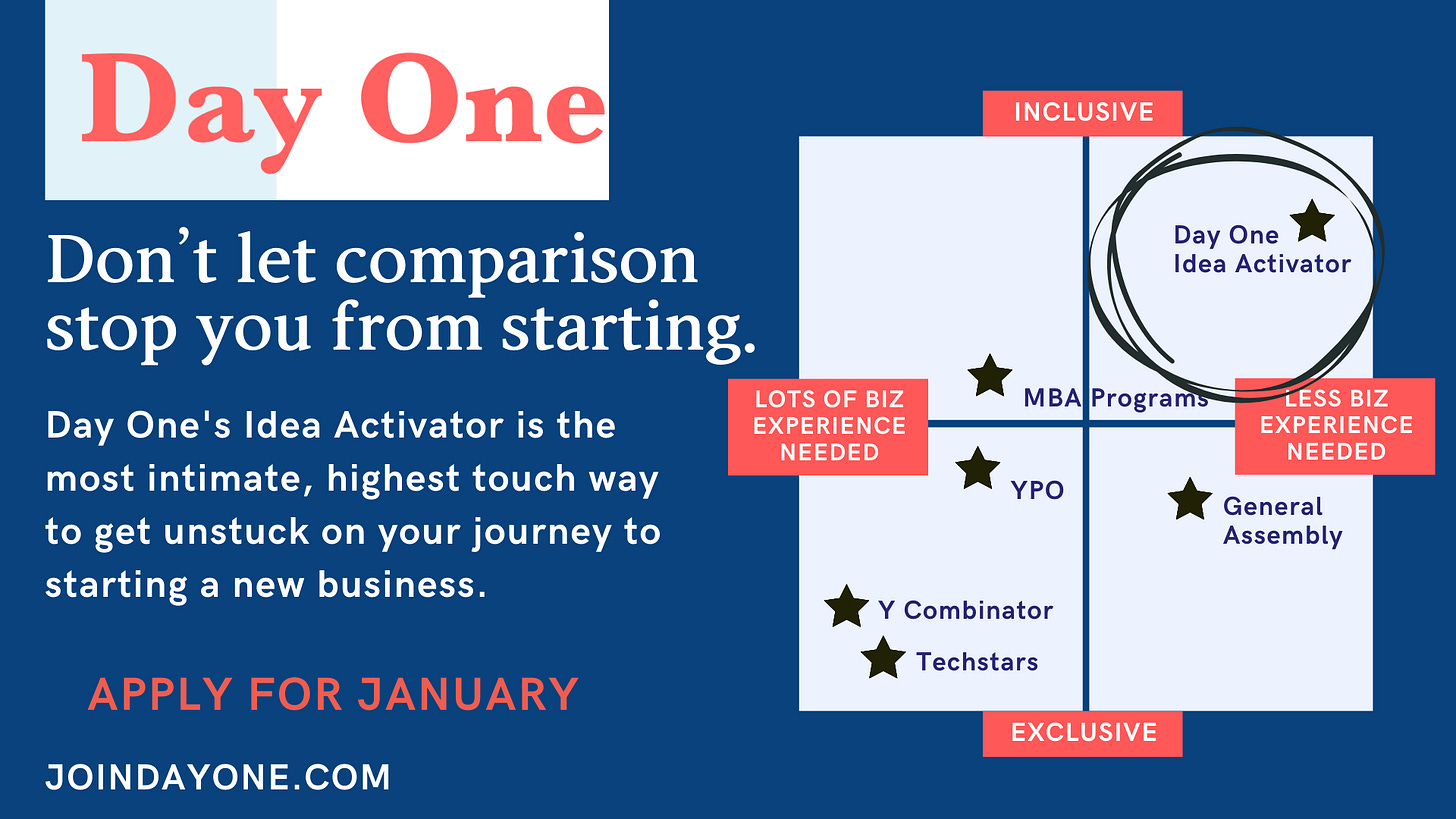

Hey PMs, Today’s newsletter is brought to you by our partner Dayone.

What is Product Pricing

Price is the only marketing mix variable or part of the offering that generates revenue. Buyers relate the price to value. They must feel they are getting value for the price paid. Pricing decisions are extremely important. So how do organizations decide how to price their goods and services?

Pricing for your products or services?

It isn’t based on how many customers you have, how many salespeople you employ, the standards in your industry — or even what you’ve changed in the past.

The best price is the amount customers will pay that effectively earns your company the maximum profit. It might be significantly higher than what you’re charging now.

Five critical Cs of pricing:

To help determine your optimum price tag, here are five critical Cs of pricing:

Company

Customers

Competitors

Collaborators

Climate

1. Cost to company This is the most obvious component of pricing decisions. You obviously cannot begin to price effectively until you know your cost structure inside out. That includes both direct costs and fully loaded costs, such as overhead, trade discounts, and so on.

And it means knowing those cost structures for each item or service you sell – not just on a company-wide or product-line basis. Too often, managers make pricing decisions based on the average cost of goods, when in fact, huge margin variations exist from item to item.

Traditionally, businesses have priced their goods and services based on their costs. But the cost is often irrelevant in the buying decision of the purchasers. They never even know the cost. Understanding this basic, yet the all-important principle is essential to determining the real profit opportunities in your business.

Your company’s gross margin potential is illustrated using the following model:

Potential sales = Units sold X customer’s perceived value per unit

Less cost of sales = Accurate direct and indirect costs of products/ services sold

Gross margin potential = Dollars left to pay all other expenses and generate profits

2. Customers. The ultimate judge of whether your price delivers a superior value is a customer. Are your customers willing to pay more than you’re charging? The information you need to know is:

What is your customer’s expected range — the highest and lowest price points?

Within that range, what is your customer’s acceptable range – the highest or lowest he or she is willing to pay?

When you consider pricing strategy, ask your clientele for their input. Two simple questions: What do you think this product or service is worth? Would you have bought it at another price?

3. Channels of distribution. If you sell through “middlemen” to get to the end-users of your products or services, those intermediaries affect your prices because you have to make their margins large enough to motivate them. You must also consider the expenses that intermediaries add. Make sure these third parties add value to the relationship between you and your customers.

4. Competition. This is where managers often make fatal pricing decisions. Every company and every product has competition. Even if your products or services are unique, make sure that you think carefully about your competitors from the buyer’s point of view (the only opinion that matters). If you’re not sure about how your customers evaluate you in terms of alternatives, pick up the phone and ask a few.

5. Compatibility. Pricing is not a stand-alone decision. It must work in concert with everything else you’re trying to achieve. Do you believe a fast-food hamburger chain can sell $10 filet mignons? Is your pricing approach compatible with your marketing objectives? With your sales goals? With the image, you want to project?

Those objectives have to be explicitly stated. For example, let’s say your production goal is to even out the process so you can better control inventory. The last thing you want is a pricing strategy that forces seasonal spikes in demand that result in stocking problems.

Before making a final decision on what to charge for your products and services, examine these five critical Cs of pricing. With the right price, you’ll generate enough fuel to power your business.

Product Pricing Strategies

New Product Pricing

With a totally new product, competition does not exist or is minimal. Two general strategies are most common for setting prices: penetration pricing and skimming

Penetration Pricing

The introductory stage of a new product’s life cycle means accepting a lower profit margin and to price relatively low. Such a strategy should generate greater sales and establish the new product in the market more quickly. Penetration pricing is the pricing technique of setting a relatively low initial entry price, often lower than the eventual market price, to attract new customers. The strategy works on the expectation that customers will switch to the new brand because of the lower price. Penetration pricing is most commonly associated with a marketing objective of increasing market share or sales volume, rather than making a profit in the short term.

The advantages of penetration pricing to the firm are the following:

It can result in fast diffusion and adoption. This can achieve high market penetration rates quickly. This can take the competitors by surprise, not giving them time to react.

It can create goodwill among the early adopter’s segment. This can create more trade through word of mouth.

It creates cost control and cost reduction pressures from the start, leading to greater efficiency.

It discourages the entry of competitors. Low prices act as a barrier to entry.

It can create high stock turnover throughout the distribution channel. This can create critically important enthusiasm and support in the channel.

It can be based on marginal cost pricing, which is economically efficient.

A penetration strategy would generally be supported by the following conditions: price-sensitive consumers, opportunity to keep costs low, the anticipation of quick market entry by competitors, a high likelihood for rapid acceptance by potential buyers, and an adequate resource base for the firm to meet the new demand and sales.

Psychological Pricing

Psychological pricing is a marketing practice based on the theory that certain prices have meaning to many buyers.

As with other elements in the marketing mix, price conveys meanings beyond the dollar amount it denotes. One such meaning is referred to as the psychological aspect of pricing. Associating quality with price is a common example of this psychological dimension. For instance, a buyer may assume that a suit priced at $500 is of higher quality than one priced at $300.

Products and services frequently have customary prices in the minds of consumers. A customary price is one that customers identify with particular items. For example, for many decades a five-stick package of chewing gum cost five cents, and a six-ounce bottle of Coca-Cola also cost five cents. Candy bars now cost 60 cents or more, which is the customary price for a standard-sized bar. Manufacturers tend to adjust their wholesale prices to permit retailers to use customary pricing.

Odd Pricing

Another manifestation of the psychological aspects of pricing is the use of odd prices. We call prices that end in digits like 5, 7, 8, and 9 “odd prices. ” Examples of odd prices include: $2.95, $15.98, or $299.99. Odd prices are intended to drive demand higher than would be expected if consumers were perfectly rational.

Psychological pricing is one cause of price points. For a long time, marketers have attempted to explain why odd prices are used. It seemed to make little difference whether one paid $29.95 or $30.00 for an item. Perhaps one of the most often heard explanations concerns the psychological impact of odd prices on customers. The explanation is that customers perceive even prices such as $5.00 or $10.00 as regular prices. Odd prices, on the other hand, appear to represent bargains or savings and therefore encourage buying. There seems to be some movement toward even pricing; however, odd pricing is still very common. A somewhat related pricing strategy is combination pricing, such as two-for-one or buy-one-get-one-free. Consumers tend to react very positively to these pricing techniques.

The psychological pricing theory is based on one or more of the following hypotheses:

Consumers ignore the least significant digits rather than do the proper rounding. Even though the cents are seen and not totally ignored, they may subconsciously be partially ignored.

Fractional prices suggest to consumers that goods are marked at the lowest possible price.

When items are listed in a way that is segregated into price bands (such as an online real estate search), the price ending is used to keep an item in a lower band, to be seen by more potential purchasers.

Other Pricing Strategies

Pricing strategies for products or services encompass three main ways to improve profits. The business owner can cut costs, sell more, or find more profit with a better pricing strategy. When costs are already at their lowest and sales are hard to find, adopting a better pricing strategy is a key option to stay viable. There are many different pricing strategies that can be utilized for different selling scenarios:

Cost-Plus Pricing

Cost-plus pricing is the simplest pricing method. The firm calculates the cost of producing the product and adds a percentage (profit) to that price to give the selling price. This method although simple has two flaws: it takes no account of demand, and there is no way of determining if potential customers will purchase the product at the calculated price.

Limit Pricing

A limit price is a price set by a monopolist to discourage economic entry into a market and is illegal in many countries. The limit price is the price that the entrant would face upon entering as long as the incumbent firm did not decrease output. The limit price is often lower than the average cost of production or just low enough to make entering not profitable. The quantity produced by the incumbent firm to act as a deterrent to entry is usually larger than would be optimal for a monopolist, but might still produce higher economic profits than would be earned under perfect competition.

Dynamic Pricing

A flexible pricing mechanism made possible by advances in information technology and employed mostly by Internet-based companies. By responding to market fluctuations or large amounts of data gathered from customers – ranging from where they live to what they buy to how much they have spent on past purchases – dynamic pricing allows online companies to adjust the prices of identical goods to correspond to a customer’s willingness to pay. The airline industry is often cited as a success story. In fact, it employs the technique so artfully that most of the passengers on any given airplane have paid different ticket prices for the same flight.

Non-Price Competition

Non-price competition means that organizations use strategies other than price to attract customers. Advertising, credit, delivery, displays, private brands, and convenience are all examples of tools used in non-price competition. Business people prefer to use non-price competition rather than price competition because it is more difficult to match non-price characteristics.

Pricing Above Competitors

Pricing above competitors can be rewarding to organizations, provided that the objectives of the policy are clearly understood and that the marketing mix is used to develop a strategy to enable management to implement the policy successfully. Pricing above competition generally requires a clear advantage on some non-price element of the marketing mix. In some cases, it is possible due to a high price-quality association on the part of potential buyers. Such an assumption is increasingly dangerous in today’s information-rich environment. Consumer Reports and other similar publications make objective product comparisons much simpler for the consumer. There are also hundreds of dot.com companies that provide objective price comparisons. The key is to prove to customers that your product justifies a premium price.

Pricing Below Competitors

While some firms are positioned to price above the competition, others wish to carve out a market niche by pricing below competitors. The goal of such a policy is to realize a large sales volume through lower prices and profit margins. By controlling costs and reducing services, these firms are able to earn an acceptable profit, even though profit per unit is usually less. Such a strategy can be effective if a significant segment of the market is price-sensitive and/or the organization’s cost structure is lower than competitors. Costs can be reduced by increased efficiency, economies of scale, or by reducing or eliminating such things as credit, delivery, and advertising. For example, if a firm could replace its field sales force with telemarketing or online access, this function might be performed at a lower cost. Such reductions often involve some loss in effectiveness, so the trade-off must be considered carefully.

In summary, the price that we pay for any given product, good, or service is the result of a series of thoughtful, well-planned strategies by the business.